When Total Return isn’t.

Is it time to reconsider how we measure stock market performance? And why you might want to exclude unrealized capital gains from your sense of wealth. Yes, I’m serious.

The issue

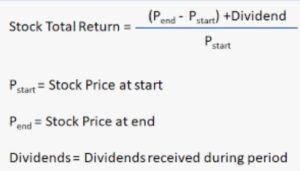

I’ve spent years arguing that stock market investors need to look more at Total Return rather than just share prices to understand the success of an investment.[i] That is because Dividend Investors in a Stock Market are regularly shortchanged by price-only stock charts and the media’s focus on by-the-minute price changes. In contrast, Total Return incorporates the income received from an investment during the measurement period. Total Return is, fortunately, still the official industry performance metric and all proper documentation of an investment in the stock market includes Total Return.

But the investment industry’s and the financial media’s mojo is clearly price change, full stop. Indeed, in a stock market yielding ~1.5% for decades, the income component of Total Return is nearly de minimis. Even stock-market products labelled as dividend can have yields of 1-2%, far from a material income stream. The SEC naming rule requires the mere existence of cashflows for such products, not their materiality. So while using Total Return levels the playing field a bit for high-dividend investors such as myself, it is just a bit.

Tilting at the Total Return windmill has left me mostly windburnt as the market has moved ever higher and yields have remained structurally low for decades. In The Ownership Dividend, I forecast a return to more normal stock market yields with a greater balance of return components. Until that happens, however, Total Return will continue to be stock-price heavy for all but a handful of very dividend-focused investors.

The problem

Still, the market’s brief hiccough in July has me rethinking the error of our collective ways. And that error is conceptually a biggie: It is treating an unrealized capital gain the same as an income distribution or a realized capital gain in calculating Total Return. These outcomes are quite different. Why are we treating them the same?

A dividend from an enterprise is a business outcome. It is not dependent on the stock market. A harvested capital gain is a stock market outcome, the result of a transaction completed in a setting entirely separate from the actual business. While both have wildly different origins, they are still real and tangible for the investor. We can consider both of them “Cash in the Kitty.”

In contrast, what is an unrealized capital gain? It is green-on-the-screen, but is it really a “return” to the investor? What has the investor actually received, as in the idea of a Return received for their Capital Outlay? Until it is realized in a settled transaction, a capital gain is theoretical and contingent; it is “Maybe Money.” It is based on what people, until that moment, have been willing to pay for an asset. But there is no guarantee that they will continue to pay that price in the future, even as soon as the next trade.

When prices are rising steadily—as they have been for the past 15 years—this contingency is not a problem. Indeed, from a psychological perspective, investors feel that they have “earned” those higher share prices through their investment acuity. Moreover, in a period of structurally low rates across the board, many investors have been using steadily rising share prices to harvest capital gains to fund their consumption. These synthetic dividends have financed the retirements of the earliest waves of the Baby Boomers, now turning 80. So in this environment—where unrealized capital gains have been abundant and easily harvested—the conflation of Cash-in-the-Kitty and Maybe Money hasn’t posed a problem.

And, of course, without the existence of unrealized capital gains, there cannot be harvested capital gains. The latter requires the former. Even a Dividend Investor in the Stock Market is looking for unrealized capital gains. As business improves over time and company dividends rise, that investor reasonably expects those company share prices to follow suit. If they did not, a high-yield arbitrage would appear. But even when an unrealized capital gain is backed by a robust and rising income stream, the capital gain is still contingent on having a buyer willing to pay up in tomorrow’s trading session and have the trade settle the day after.

So the issue is not the goal of share prices moving up and to the right—the natural state of affairs over long measurement periods where real growth and inflation both have positive values. Instead, it is how we characterize this in-between state of nature. How should we acknowledge the difference between a return directly to the investor, and one that is just in the market?

This characterization is particularly worthy of review because when share prices are falling—as they do now and again—neither the psychology nor the math of unrealized capital gains is quite as appealing. In a red-price context, the contingent nature of an unrealized capital gain becomes much clearer. Watching a contingent capital gain turn into a contingent capital loss can be a jolting experience. And while realized capital losses are just as real as the rest of the Cash-in-the-Kitty—and can be used to fund a more modest consumption or limited reinvestment—they don’t have the same allure as realized capital gains.

The tax code appreciates the difference between the types of return. It only recognizes Cash-in-the-Kitty—dividends and harvested capital gains or losses. It generally pays little if any attention to Maybe Money. But this partial sobriety on the part of tax man makes the current Total Return calculation all the odder. It is—as it were—half taxable and half not. Some recent out-of-left-field proposals to tax unrealized capital gains are illogical, given the contingent nature of those returns. The mismatch does not require a change to the tax code. Instead, it is an invitation to reconsider how we define our investment results. As things stand now, investors are encouraged to subordinate investment policy to tax minimization. Those so inclined will lean toward unrealized capital gains with as little taxable dividend income as possible in taxable accounts. There’s nothing wrong with this segmenting of investment activity, but the heavy hand of tax minimization does impact the price discovery and capital allocation function of the market.

The financial services industry has long structured products around the difference between realized and unrealized gains. Mutual funds treat realized returns identically: income and capital gains both get distributed and taxed. Unrealized capital gains are retained and untaxed. The now fashionable ETF structure bends over backward to avoid realized capital gains being distributed and therefore taxed. Were it not for those contortions, ETFs would treat income and realized capital gains the same way mutual funds do.

The world of Private Equity is very much based on cash returns. It uses borrowed money to strip and flip businesses. Cash in; cash out. While Private Equity funds must report carrying values of their current holdings—a weak input to determine intermediate-term returns—those numbers are held in little esteem. In a much less sinister manner, most private businesses are run on a cash outcomes basis. To be fair, they do so because they don’t have a daily market price as stocks do. But the absence of those markets makes it very clear what the purpose of a for-profit enterprise is: to generate distributable cash.

Real estate is another example where one can contrast a Maybe Money nominal outcome with a realized Cash-in-the-Kitty return. Yes, there is a market for real estate assets, which is important when you enter and when you exit years later, but in the interim, the property’s cashflow is the measure of the investment’s health. If it is rising in line with expectations, all is good. The same cashflow-based math extends to your own home. Let’s say you think your house is worth $1 million. It’s not worth a penny until you sell it, no matter what an on-line real estate service might suggest. (You can borrow against your house, but your bank will not loan you anywhere near a million—except during the occasional housing bubble and banking delirium.) But if you rent out your house and get $5k per month net of all expenses, for $60k a year, and use a discount rate of 6%, yes, your house is worth $1,000,000. In that way, you’ve turned a Maybe Money value into a Cash-in-the-Kitty real return. Let’s say you don’t have the luxury of renting out your house. In that instance, government statisticians get around the tricky nature of a contingent value by coming up with a theoretical income stream—Owners’ Equivalent Rent—to use in the national accounts.

The point is that for assets without the benefit of a liquid, daily market, unrealized capital gains are not only contingent, they are hyper-contingent. That fact alone should suggest some circumspection about how we treat a similar situation in the stock market.

Is the gap in practices perhaps context specific? From my perspective, yes. Unrealized capital gains are especially contingent when they are completely untethered to income streams. This was not always the case in the stock market. Up until the 1980s, all major issues that were not clearly speculative or in obvious distress paid dividends, usually material ones. As the dividend rose over time, share prices followed a similar trajectory.[ii] Capital gains were still contingent until realized, but the math of contingency was different. There was a clear linkage between realized gains (payment and growth of the dividend) and the unrealized gains of share appreciation.

But for the past 30 years, we have been in a declining yield or just an outright low-yield stock market. There is no cash “anchor” on the rocket ships leading the market ever higher. Stock market investors will point to P/E ratios or some other valuation metric, but those are not measures of returns. They are not returns at all. Critics will suggest that investors are paying for future cashflows and that those future dividends—realized returns—will more than equal the current price. Yes, I’ve been told that hundreds of times. Investors have waited decades for that math to work out, and may have to wait decades more.

The remarkable price gains of the leading technology issues might be considerably less contingent if they all paid 4% yields and were growing the dividends at the same rate as earnings. In that instance, their unrealized capital gains would be intrinsically linked to their cash returns to long-term shareholders, with the contingency just a matter of the settled transaction. But they don’t pay 4% dividends. So the Maybe Money nature of their gains is all the greater than it was prior to this period.

At the other end of the spectrum, buybacks are the ultimate exercise in contingency. Academic finance treats them in a blasé manner as a return to the investor identical to a dividend. But not only are buybacks a market exercise distinct from the business, they are not helpful to investors unless those investors become sellers. And in that case, investors have to sell shares and hop over the contingency “wall” to a realized capital gain or loss. But for the investors who remain, it’s hard to characterize buybacks as any type of return at all. In theory, if the buyback results in a lowered share count—that can happen—the remaining investors’ stake in the company has increased, giving them more future dividends. But, oh my, there are a lot of steps, or shall I say contingencies, along the way to those greater realized returns? My purpose here is to clarify and improve our understanding of investment outcomes. In contrast, buybacks muddy the waters.

History

If the current definition of Total Return is, to say the least, a peculiar amalgam of outcomes, why hasn’t this issue been raised before? I’ve been unable to find an issue of the Financial Analyst Journal (1945) or even the later Journal of Portfolio Management (1974)—the industry’s two leading practitioner journals—or any other moment in time dedicated to defining and canonizing Total Return and addressing the contingent nature of “half” those returns.[iii]

Without a clear lineage, the definition of Total Return creeps into popular usage in the 1960s and 1970s as the data and calculating systems needed for it became more widely available. If you scan business and economic journals of the 19th century and early 20th century, the term total return has a materially different definition, more akin to net income in a business enterprise. It can also mean the percentage return on capital put into an enterprise, including debt as well as equity. In those instances, it is calculated using the coupon on the debt portion of the invested capital and the dividend yield on the equity or preferred equity portion. That is, the total return is very much a cash-based concept. Change in asset price is rarely, if ever, mentioned. And for good reason. Reasonable databases of confirmed asset prices were simply not widely available at that time. And as much as the assumption behind non-speculative investment was about the coupon-based return, there would be less incentive to closely track long-term price changes or incorporate them into a popular understanding of investment outcomes.

As the 20th century proceeds, however, examples of Total Return as we currently define it begin to appear in the financial media. In those instances, it is a matter of simple math, without compounding, without annualization or any other of the ways that Total Return is now calculated and represented. In his landmark 1924 study of investment results, Edgar Lawrence Smith takes the market value of a basket of securities in two points in time, figures the dollar value of the difference. He then adds the income received in that period to produce a dollar value of gain in the portfolio. There is no annualization using geometric compounding or reinvestment of dividends. It is just simple arithmetic measures of average annual return based on aggregate dollar values. But he does include both components, income received and price changes. He concluded that “In the selection of securities for investment, we must consider more than the expected income yield upon the amount invested, and may quite properly weigh the probability of principal enhancement over a term of years without departing from the most conservative viewpoint.”[iv]

A decade later, Ben Graham also falls into the anecdotal category. In Security Analysis, he cites the combination of dividend return and price changes in his various analyses, but it is not used as a systematic measure of investment outcomes.[v] (His contemporary John Burr Williams leaned in the opposite direction, separating investment—dividends, coupons & principal—from speculation—resale price.[vi]) T. Rowe Price, Jr. referenced price gains and income gains, but kept them separate in his argument in favor of growth stocks in a series of articles for Barron’s in 1939.[vii] The Cowles Commission All Stock Index, created in the late 1930s, made an effort to capture both forms of return—”increase in market value” and “yield or ratio of cash dividend payments to stock prices” and used the term “total return” in an approximation of its modern sense. Alfred Cowles wrote that “If we added cash dividend payments to changes in the market value of stocks, determined as described above, the total return has been ….”[viii]

In the post-war literature, capital appreciation nudges income aside as share-price gains began to outshine the value of coupon payments. In their 1959 work comparing “growth” and “income” portfolios, David and Thomas Babson created a $10,000 basket of stocks and then looked at it a decade later. They tallied up the gain in market value. Then they took the dividend income that each portfolio had for that period. They simply added the two figures together to come up with a simple “gain in value plus dividends.”[ix]

By the 1960s and 1970s, as the tools for investment measurement (price data sets and calculating ability) improved dramatically, the period of anecdotal Total Return calculations came to an end. Instead, a growing number of serious studies of investment returns appeared and necessarily used Total Return calculations that we would recognize today. Fisher & Lorie’s famous mid 1960s study of rates of return of common stocks from 1926 through 1960 included both dividends and capital appreciation.[x] The equally prominent work of Robert Ibbotson and Rex Sinquefield featured analysis of “total rates of return which reflect dividends or interest income as well as capital gains or losses…”[xi] In one of the pathbreaking studies of mutual fund performance from 1966, William Sharpe takes the time to define fund return as “the sum of dividend payments, capital gains distributions and changes in net asset value.”[xii]

This professionalization of investment measurement did not go unnoticed. Richard Jenrette (cofounder of DLJ) gave a speech in 1966 in which he suggested that it was time for professional money managers to “start keeping score.”[xiii] Testifying before Congress in 1969, an industry participant stated that “I think if you were to talk to most of the banks and pension plan people around the country, you would find that this new notion of total return is the way they look at the return on their investments.”[xiv] Even conservative endowment managers could no longer ignore the risk of missing out on the stock market’s new emphasis on capital appreciation in the go-go growth 1960s. By the mid 1970s, a writer in the Journal of Portfolio Management warned that missing out on growth stocks could “seriously inhibit the endowment fund’s total rate of return (that is, yield plus appreciation.)”[xv]

At about the same time, the SEC began consideration of including Total Return in mutual fund documentation “giving mutual funds and variable annuities the opportunity to portray past Investment results in terms of compound rates of total return (assuming dividends and capital gains are reinvested).”[xvi] A decade later, in the late 1980s, the government finally formally got around to defining Total Return as the benchmark performance measurement for equity mutual funds.[xvii]

In this context, the fact that Total Return was “half taxed, half not”, half Cash-in-the-Kitty and half Maybe Money should not have bothered anyone. Measuring Total Return in this way was a vast improvement over what went before, which was the absence of any systematic, consistent measurement of investments. Moreover, while there were (and still are) other, perhaps better measures of investment performance for a venture (ROIC, IRR, DDM, EVA, etc), Total Return addressed the unique challenge—brewing for centuries, but coming to a head in the mid 20th century—of measuring the outcome of an investment that has a daily market price as well as a cash-on-cash component.

In that regard, the widening of stock market ownership in the 20th century, the institutionalization of prices, the emergence of regularized financial reporting, etc made measurement designed to address this particular form of investment quite necessary. Indeed, Total Return represented the only form of performance measurement that could be calculated on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis in a meaningful way. It didn’t hurt that growth was all the rage after World War II. In that context, the shift from the prior, heavy-on-the-income forms of looking at investment outcomes to the heavy-on-the-price-change approach made sense. How not to account for our brave new post-war world? Total Return did.

The question is 70 years later, when that “newness” factor is no longer new, is Total Return still the best way to measure stock market outcomes? More importantly, is it contributing to outright speculation, unnecessarily low actual investor returns, and capital misallocation that can impact the real economy? If simple total return was Version 1.0 (1920s-1950s), and modern Total Return 2.0 has served well and long (1960s-2020s), is it worth keeping this B-52 in the air for another half century without considering some modification?[xviii]

As I argued in Getting Back to Business from 2018, Modern Portfolio Theory emerged at roughly the same time and for roughly the same reason: it fixed a problem—the absence of any portfolio theory—with a very basic solution. Developments by Markowitz in 1952 and 1959 were made vastly more applicable by William Sharpe and others in the mid 1960s. By the 1970s and 1980s, the ability to manage portfolios in a manner heretofore impossible became widespread. As in the case of Total Return, I have asked whether 70 years later, MPT is still fixing the original problem, or whether it has created new challenges.

The Proposal

The proposed refinement of Total Return is mostly one of semantics and emphasis. Cash Returns would include income payments and realized capital losses and gains. Contingent Returns would show unrealized capital gains. Total Return would remain the combination of the two. From a reporting perspective, it’s not that big of a departure from current practice. Most brokerage reports already show unrealized capital gains. Only a little math is required to tally just income received and realized gains or losses as Cash Returns and show them alongside the Contingent Returns in a given measurement period. (The math for multi-period analysis gets trickier, because both types of return in a prior period become the cost basis for the new period, but it is something simple calculating formulas can handle.) Institutional investors already know their unrealized and realized capital gain position at any time.

Viewing investor returns this way would also not really change how we look at individual securities or even indices. There already is an income and share-price component to Total Return when applied to them. This would simply make clear to investors and analysts the relative proportion of one to another in any given measurement period.

Implications

While the reporting would be only slightly different, the implications for investor psychology and perhaps investor practice could be far greater. I would go so far as to suggest that the move might lead to greater investor sobriety and less value-destroying speculation, but that’s setting a high bar. Still, as various commentators consider measures to offset the excessive “financialization” of stock market returns during the past several decades, it is worth considering adding some nuance to Total Return as part of that effort.

Perhaps the most important implication would be a prospective shift in the popular understanding of wealth. Economists have narrow definitions for this term, but the common-sense understanding of these ideas today leans heavily in the direction of unrealized gains. In contrast, until the most recent era, income-producing assets were the driver of how wealth was defined and understood. Mr. Darcy had 10,000 pounds per year, while his friend Mr. Bingley got by on a mere 5,000. Emergent academic finance in the late 19th c and early 20th century also sided with the income orientation of wealth.

With the widespread development of stock markets in the 20th century, however, it become possible to understand wealth in terms of the market value of assets. As I observed earlier, since most serious stock holdings came with material income streams up to the 1980s, the contingent nature of those asset values was less problematic. (The 1920s showed, of course, that there is always room for speculative periods.) But that is no longer the case. Vast fortunes now consist almost entirely of unrealized gains in non- or de minimis- income-producing assets. Counting them as Contingent Returns compared to Cash Returns is not intended to diminish the accomplishment of such outcomes, but simply to remind investors of the cold hard fact that Cash-in-the-Kitty and Maybe Money are different. The market’s periodic downdrafts make that point more dramatically. Having the counting system acknowledge the difference is additive to investor understanding of markets.

While adding some needed subtlety to our understanding of wealth, redefining investment returns would also shed further light on actual investor outcomes. There already exists a sub-genre of literature on actual investor returns and how they are lower than market or index or fund returns because investors time their buys and sells poorly. (Morningstar’s annual “Mind the Gap” report does a good job in periodically producing and distributing this research.)[xix] Incremental appreciation of Cash Returns rather than Contingent Returns focus doesn’t fix the problem of disappointing investor experiences, but it might help investors better understand the challenge of market timing.

As in the case of investor returns, using a more granular approach to investment returns might improve investor understanding of executive compensation packages. For the past several decades, those packages have often been based on TSR (Total Shareholder Return) relative to industry peers. Breaking Total Return into its component parts should be seen as an augmentation of that process.

As an added benefit, separation of the two types of return might also shake up a key component of modern academic finance. That is because the Standard Deviation of Cash Returns is almost always going to be lower than that of Contingent Returns. Since Standard Deviation is central to many of the ratios and statistics used to judge investment outcomes (and lower is generally better), highlighting the lower volatility of Cash Returns may also affect investor behavior.

Finally, does the conflation of unrealized capital gains and wealth contribute to the “financialization” of investment—stock market returns exceeding and increasingly detached from real economic gains? It’s hard to see how it doesn’t. Wall Street engineering that boosts share prices and executive compensation with commensurately less impact on the real economy is now a political issue. Being a little more careful in how we define and measure investment returns isn’t going to quell all the critics, but having more information about the nature of those returns might contribute to better analysis of the issue.

Objections

The prospective downsides to this approach need to be acknowledged. The first is taxation. Cash Returns are taxed; Contingent Returns are not (for now). Splitting the definition of Total Return might mean greater taxation for those investors who choose to lean toward Cash Returns. For other investors, that is a non-starter. Those insistent on subordinating investment policy to tax minimization will continue to favor Contingent Returns. Similarly, for those fortunate investors not needing current income and taking a very long view, yield-on-cost opens the door to a strong preference for Contingent Returns. While the marginal dollar going to Apple or Microsoft today gets only a 1% yield, those names held for years have yield-on-cost figures that are much more reasonable and can perhaps justify the contingency of their substantial unrealized gains.

The second, related issue is excessive trading. A greater spotlight on Cash Returns might lead investors to trade more in an effort to lock in those dollars. While I am sympathetic to the goal, the practical result would be higher turnover and perhaps equally bad investor timing as before. That remains to be seen, but it is an obvious risk.

A third possible objection is that the investment management industry is generally paid in terms of overall asset levels, including both realized and unrealized returns. Considering the two components of return separately does not imply a change in an industry’s fee structure. Indeed, it should help investors better understand what they are paying for and perhaps express a preference for one or the other.

Critics will also point out that earnings growth, not multiple expansion, is the main cause of the bountiful unrealized capital gains we have seen in recent decades. Increased profits make those gains less contingent than they would be if just from multiple expansion. This is certainly true, to a point. Earnings can be engineered. Distributed cash and realized gains cannot (beyond a certain point). Earnings growth is more of a high-grade literature than pulp fiction multiple expansion, and can be compelling enough to support high valuations, but it is fiction all the same. Cash generation is a fact.

Finally, why propose a system of greater clarity and distinction between Cash Returns and Contingent Returns for younger investors who have no need for consumption from their investment dollars. For them, there is simply no problem here. And if they are lucky or skilled enough to find the next Nvidia, they have no particular need for greater cash returns or a measurement system that highlights them. Similarly, most passive investors couldn’t care less about any of this. They’re not reading this essay, and they are utterly indifferent to the inside-baseball nature of investment measurement. As long as the market is going up over time, they have no interest in business ownership through the stock market.

Conclusion

These shortcomings aside, it is always worth asking whether a central analytical tool that we use on a daily basis remains fit for purpose given that it was created decades ago to solve a problem particular to that time. Daily measurement of investment outcomes obviously still serves an important function. But it is far from clear that Total Return should be the sole canonical measurement tool, particularly when a high percentage of it is comprised of unrealized capital gains.

Such a view will curry no favor on Wall Street.[xx] That too is revealing. I look forward to sorting through the barrage of dismissals to find what I hope will be a handful of more serious rebuttals justifying the admixture of realized and unrealized returns. At the end of the day, however, it is likely to be a matter of philosophy, not finance. Dividend Investors in a Stock Market take business ownership seriously. For us, the nature of returns matters a great deal. As currently defined, Total Return conflates a business outcome with a market outcome. We can do better.

[i] The views expressed here are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the views of his employer or anyone else cited in this essay. Consult your financial advisor before making any investment decisions that might have been influenced by the arguments presented herein. The purpose of this essay is to generate discussion about industry measurement tools. It is not intended to promote any particular investment products.

[ii] See Peris, The Dividend Imperative (McGraw-Hill, 2013), 35-43.

[iii] As I was working on this piece, Hendrik Bessembinder and team placed an article on SSRN entitled “How should investors’ long-term returns be measured?” It is slated to appear in an upcoming issue of the Financial Analyst Journal. In it, the authors introduce the concept of “’sustainable return,’ defined as the rate of periodic withdrawal for consumption consistent with the preservation of real capital.” See Bessembinder, Hendrik (Hank) and Chen, Te-Feng and Choi, Goeun and Wei, Kuo-Chiang (John), How Should Investors’ Long-Term Returns be Measured? * (August 20, 2024). SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4528681 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4528681 My thanks to Hunter Hopcroft for directing me to this piece.

[iv] Edgar Lawrence Smith, Common Stocks as Long Term Investments (New York: MacMillan Company, 1928; originally published in 1924), 80. It is not clear if dividends are reinvested, but is suggestive that they are not.

[v] Benjamin Graham & David L. Dodd, Security Analysis, 6th edition (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008), example at 377. The 6th edition is based on the 1940 2nd edition, with additional commentary.

[vi] John Burr Williams, The Theory of Investment Value (1938), 4, 34.

[vii] T. Rowe Price, Jr., “Picking ‘growth’ stocks,” in Classics: An Investor’s Anthology, ed by Charles D. Ellis (Homewood, IL: Business One Irwin, 1989), 113-121.

[viii] Alfred Cowles 3rd & Associates, Common Stock Indexes 1871-1937 (Bloomington, IN: Principia Press, 1938, as cited in Charles Ellis with James Vertin, eds., Classics II: Another Investor’s Anthology (Homewood, IL: Business One Irwin, 1991), 474.

[ix] David L. Babson & Thomas E. Babson, “Is growth stock investing effective? Some guides to successful lifetime investing,” in Charles Ellis, ed., Classics: An Investor’s Anthology (Homewood, IL: Business One Irwin, 1989), 173-191. Reprinted from their Investing for a Successful Future (MacMillan, 1959).

[x] Lawrence Fisher & James Lorie, “Rates of Return on Investments in Common Stocks,” The Journal of Business, Vol. 37 (January 1964), 1-21.

[xi] Roger G. Ibbotson & Rex A. Sinquefield, “Stocks, Bonds, Bills, and Inflation: Year-by-year Historical Returns (1926-1974),” The Journal of Business, Vol. 49 (January 1976), 11-43.

[xii] William F. Sharpe, “Mutual Fund Performance,” in Edwin J. Elton & Martin J. Gruber, eds, Security Evaluation and Portfolio Analysis, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc, 1972), 576, reprinted from the Journal of Business: A Supplement, no. 1, part 2 (January 1966), 119-138.

[xiii] Richard H. Jenrette, “Portfolio Management: Seven Ways to Improve Performance,” in Ellis, ed., Classics: An Investor’s Anthology, 382-391.

[xiv] Hearings Before the Committee on Finance , US Senate, Tax Reform Act of 1969. H.R. 13270, page 6094.

[xv] J. Peter Williamson, “Endowment funds: Income, growth, and total return,” Journal of Portfolio Management, Vol 1, no. 1 (Fall 1974), 74-79.

[xvi] Annual Report of the SEC for the Fiscal Year ended June 30, 1975, 26-27.

[xvii] Securities and Exchange Commission. (1988, February 10). 17 CFR Parts 230, 270, and 274. Advertising by Investment Companies [Release Nos. 33-6753; IC-16245; File No. S7-23-86] 53 FR 3868.

[xviii] While the Total Return calculation used in this essay is the simplest variant, there are complexities behind the formula, particularly measurements over long time periods involved reinvestment and compounding. See Bessembinder, et al, esp. 33.

[xix] How Does the Timing of Fund Selection and Sale Impact Investor Returns? | Morningstar ( https://www.morningstar.com/insights/2019/08/30/investor-returns-fund ) and Why Fund Returns Are Lower Than You Might Think | Morningstar ( https://www.morningstar.com/funds/why-fund-returns-are-lower-than-you-might-think ), and most recently, Mind the Gap 2024: A Report on Investor Returns in the US | Morningstar ( https://www.morningstar.com/lp/mind-the-gap ) and Mind_the_Gap_2024.pdf (contentstack.io)

[xx] My thanks to those colleagues and market participants who reviewed, and energetically criticized, earlier versions of this article.

(Image courtesy moneyinvestexpert.com)